9 Mile Road Adventure

by Rob Tucker

Reprinted from "Crown Jewels of the Wire", July 1997, page 30

There was an air of quickening anticipation as the car turned into the

growing shadows spreading across the parking lot at Dinosaur National Monument

outside of Vernal, UT. The jagged, upturned sedimentary rocks entomb the

skeletons of many hundreds of long extinct dinosaurs and as many scientists have

pecked away at the encasing sandstone. My family had ventured to these same

craggy rocks when I was ten or so, about the age of our daughters, and they now

were wondering (as I did so many years ago) why were we here. It took only

fifteen seconds and we were all hooked at seeing the mighty beasts and bones.

It

sometimes takes a bit of bribing to get the family on the trail of the

insulator. This trip was no real exception: we would do dinosaurs on Saturday

and then on Sunday, drive down Nine Mine Road to see the old insulator line on

the way back to Salt Lake City, throw in a Happy Meal at McDonalds and the

weekend would be complete.

This part of Utah is starkly beautiful and a bit

isolated even today. The history of the area is full of colorful characters from

"Utahraptor" to Butch Cassidy to the forgotten mule skinner, mail

courier, and school marm who all have made a mark on the land but have not tamed

her harshness or ever changing beauty. There are ancient petroglyphs (carved

into the desert varnish on the rocks) and pictographs (paintings) in nearly

every canyon. The Utes lived here when the white man came. The Indians and a

collection of outlaws, settlers, ranchers, and a few Army troops all kept a

rough and tumble peace between themselves and each other for many years. In

1885, intertribal war broke out among the Utes that upset the balance. To keep

the peace, in August 1886, two troops of the all black 9th Cavalry under Maj.

Benteen and four companies of white infantry under Cpt. Duncan arrived to help

quell the hostilities. The reception party of 700 rather angry but wary Utes and

the heavily armed but outnumbered soldiers made a quick peace. The soldiers

built a hasty camp on a sage covered bluff that would became Fort Duchesne.

The

soldiers of the 9th Cavalry set about building a wagon road from their remote fort to the railroad junction in Price. The soldiers

also needed quick and reliable communications with the outside world and

constructed a telegraph line. And this is the part of the adventure that deals

with some of the most sought after gems in our hobby, the purple CD 126 blob

tops. The Army did not want to spend money on wooden poles when there were miles

of three inch pipe rusting in Eastern storage yards. The pipe moved west by

train, the blacksmith put a metal dowel through the pipe about four feet down

from the top to support the lineman and the wagoneers began hauling the iron

poles up the new road for installation along the eighty or more miles from Price

to Fort Duchesne. (Why it's named Nine Mile Road is another story).

The

soldier's road is still a dirt track through the canyons and high plains and

many of the poles are still in place from north of the Nutter Ranch to Soldier

Creek Summit. I had been told these poles were still standing and that some

insulators were still on them. Now dreams of purple blob tops hanging out on an

isolated pole cruised through the dreams all the night while trying to get some

sleep in a Vernal hotel room. All that day my eyes strained to see through the

road dust to catch a glimpse of an iron pole standing sentinel on the desert

floor.

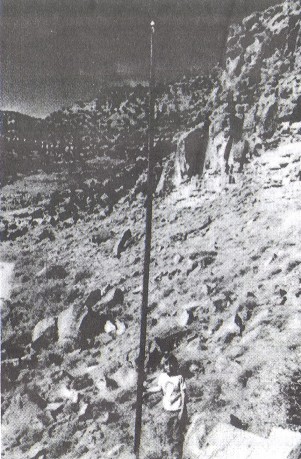

Perianne Tucker at original relay station

on telegraph line between Fort

Duchesne

& Price, Utah near Nutter Ranch.

I had talked Syndia into driving so I could have a better look and read

the tour guidebook of the Nine Mile Road. When I saw the first pole my heart

raced into high gear and as I shouted to stop, the startled driver threw the car

into a four wheel lock up slide, coming to a halt on the side of the road in a

billow of dust. Syndia slumped over the wheel in an adrenalin rush flashback while the

kids and I raced up the hill to see the pole and the insulator on it. But alas,

there was only a rubber piece on the peg. We got several pictures of the poles

tramping out across the sagebrush flats and fading into the distance. We hunted

around the base for a bit and came up with one small light aqua shard that may

have been a Brookfield blob top. There were quit a few tourists on the trek,

taking in the many Indian petroglyphs on the rock walls, the old ranch

buildings, and even a site where outlaws were to ambush an Army patrol carrying

the entire payroll.

We reached the Nutter Ranch about two in the afternoon. It

was here that a relay station was built. The small rock building with roof is

still standing, long after the last electrons were sent on their merry way

through the wires. The original double set of telegraph wires was replaced with

a single wire sometime after the fort closed in 1912. The new users had to

replace many insulators too. The older Hemingray 16s were replaced with aqua and

clear Hemingray 42s and clear Hemingray 45s.

A lone Hemingray-16 on an original pole

on the way to Soldier Creek Summit.

The day was beginning to wane as we

headed on to Soldier Creek Pass with a decided chill in the winds that swept

down the narrow valley hemmed in by the massive sandstone walls. Then a sparkle

caught my eye from way across the valley. It was one lone pole with a sparkling

gem gleaming away in the setting sun's glow. With a few extra entreaties to my

steadfast driver the car rumbled to a halt. I had five minutes to see the pole

and be back ready to roll. I darted across the road and was ready to descend the

banks of the creek when my enthusiasm was halted in mid stride. The small creek

we had been following for a ways had carved some mighty steep walls in the soft

valley sediments. The creek was still small as it meandered along away down

below, about 100 vertical feet below from where I now stood. My time was a ticking, and

there was a barely passable slide area a few yards away and like an airborne

fool I took that first step and careened down the slope. Most of the far side of

the creek was cut from the sandstone layers that were a bit easier to scale. The

pole, however, was plunged into almost solid rock and standing more out of spite

than depth. Within a few feet of the wiggly-wobbly pole was another sheer

dropoff, and there were big sharp rocks below. Now I did test the pole with a

casual jump up but quickly decided that this piece would not adorn any of my

shelves. Now if there had been an ancient jewel atop the pole I would have

figured out a method to outwit gravity and begged forgiveness on being outside

of my five minute window.

I have seen one of the purple blob top jewels and was

impressed by its deep color and awed by its place in history. There are probably

a few of these rare gems in someone's attic but teasing them to the light of day

will be a hard trick.

I have since had many hours to ponder the paradox of

purple blob tops coming from the West. In looking over McDougald's Insulators,

Volume 2, there are only two embossing variants that occur in purple. Is it

possible that only these two mold variations ever had the correct melt mixture

run through them that would produce a purple insulator? The chances of this

happening seem vanishingly slim knowing the large numbers of these insulators

produced over an extended period of time. There is a mystery here that needs

some more sleuthing. From the few clues I have at my disposal, I may have a

partial answer that I would like to share and get some feed back from other

collectors.

Let's start with a few known facts. 1. The CD 126 began production

in the early 1870's based on the patent dates and continued until at least circa

1887 when the road and lines were constructed.

2. The Brookfield Company began

producing the new Oakman insulator style described as a "paraboloid

traversed by an equatorial groove" (our beehive) sometime shortly after

1884. There is then a production overlap of CDs 126 and 145.

3. There were many

pistol totin' hombres, itinerate miners, hot shots like the Sundance Kid and

poor shots (even maybe my grandfather who could have wandered this trail enroute

to buy cattle for a Montana drive), and the forbidding weather which all

probably conspired to make the life of an insulator rather short. Replacements

were always needed.

4. I have been in the Army some 12 years and believe that

understanding the Army supply system is a factor in solving the purple paradox. The Army supply system does not like change because it takes

so long to get a product in the system (true then and true now). It would have

been virtually impossible to buy an insulator "off the shelf'. The process

would have gone something like this: A group of officers began a study on what

was needed to define what an insulator needed, to meet the needs of the Army;

then a report was written proposing a staff study to review the proposal and

another group of officers to include the quartermaster who coordinated getting a

good price, added to the report. This report was sent to some general who held

it the appropriate time, then sent it to the War Department in Washington who in

turn studied it, staffed it etc. etc. Process time was at least one to two years

just to get an insulator. My guess is that when insulator X got into the Army

supply system, virtually all insulators bought by the Army would have been

nearly the same for a long time and/or provided by one supplier.

Perianne Tucker by pole in Nine Mile Road.

Another

important facet of the Army supply system is the need to buy something that

could not be readily used by the civilian population and/or was distinctively

Army. This keeps the theft of Army property to a minimum and allowed for easy

identification of the property (done then and done now). For example, a barrel

of hardtack would not be readily stolen because no one really wanted to eat them and if you had them, it was easy to

determine who the rightful owner really was.

Given these supply type criteria,

it would seem logical for the Army to get a long term contract with Brookfield.

It is easy to see that in 1887-89 the CD 126 would still be used even though the

rest of the nation was going to the new CD 145. (Same then, same now. Imagine

the turmoil the changing computer technology causes the Army). These first

insulators were probably aqua CD 126 with a few greens from Brookfield's reknown

quality control.

5. Robert Good and/or the Valverde, CO glass works produced

insulators from 1895 to 1909. Denver would have been a logical choice to order

replacement insulators due to its close proximity to many Western forts. The

purple CD 126 I saw has the color characteristics common to other Denver

products.

Now for some jewel sleuthing. If I were setting up a new business in a

far away place like Denver, it sure would be good for business to get a

Government contract (good then, good now). The Nine Mile Road was a hopping

place during this time and insulators were probably falling pretty regularly.

Suppose the Army still wanted the CD 126 because it was "in the

system" and no one else was using them so theft would be a minimal problem.

Suppose Mr. Good wanted the Army insulator contract and that the Brookfield

Company wanted to quit making an obsolete design and shipping the pieces clear

across the nation at a by now low price. It is possible that Mr. Good bought the

few remaining CD 126 molds from Brookfield and produced a limited number of

insulators for only one customer -- the Army (at a price that made the venture

worthwhile). This could explain how only two embossing variations end up being

found on purple insulators, that I think, come pretty much from the West. This

also could explain how a CD 126 appears to be made well after its otherwise

normal life cycle.

Now the question is, how to get more information on this subject? Anyone have

some ideas?

Editor's note: This great article got wedged in a wrong vertical file and

waited a long time for printing. My apologies to the Tucker family, and to

Perianne who, I am sure, is ready to graduate for high school.! Well, that is a

bit of an exaggeration!

|